Read part one of this post here.

During the first part of this article we covered a lot of ground. We established that in order to hit what you’re aiming at with a handgun, the bore must be aligned with your target. We determined that sights and optics are put on firearms in order to align the shooter’s eye with the bore. Also, buying new sights or optics does not make your gun “more accurate.”

In addition, we took a deep dive into the biology of the human eye and how normal human vision works, particularly with regard to foveal vision and focus. Let’s not forget central fixation bias or our eye’s natural, built-in tendency to center that which we focus on in our vision. As long as you deliberately focus on the front sight while looking through your rear sight, the front sight will be centered.

Finally, in part one we were able to determine, based upon how human vision works and the actual science of sight, the best or most useful iron sight design. For handgun sights, the best design is a front sight that’s easy to see and that reflects the most light combined with a rear sight which is uncomplicated and does not distract our eyes from seeing and focusing the front sight, the most important of the two. Rear sights are meant to be looked through, not looked at.

Vision Complications

It’s a reality of aging that as we grow older, our vision tends to change. Many years ago, it was explained to me that the average man over forty needs four times the amount of light to see things clearly in low light conditions as a healthy man does at age eighteen. Some folks are blessed with clear vision well into their golden years. Many are not.

As we age, our eyes tend to gravitate toward either farsightedness or nearsightedness. Nearsighted simply means that objects that are close are clear in your vision while distant objects are blurry. Farsighted people have no trouble seeing distant objects, but they need to squint or put on glasses to read a book or look at their phones.

When I was a twenty-year-old young man, I could see the front sight post on my M16A2 with crystal clarity and line it up on a 500-yard target without a problem. Not so much today. For those who are getting long in the tooth, seeing a front sight clearly now might require corrective eyewear.

One of the complications with modern prescription glasses is the use of bi-focals or progressive lenses. The near or close-up part of the lens is at the bottom and the distance viewing part is at the top. However, when we’re aiming a handgun, we extend our arms and tuck our chins, that puts the distant viewing part of our prescription glasses in line with our sights. That can be a problem.

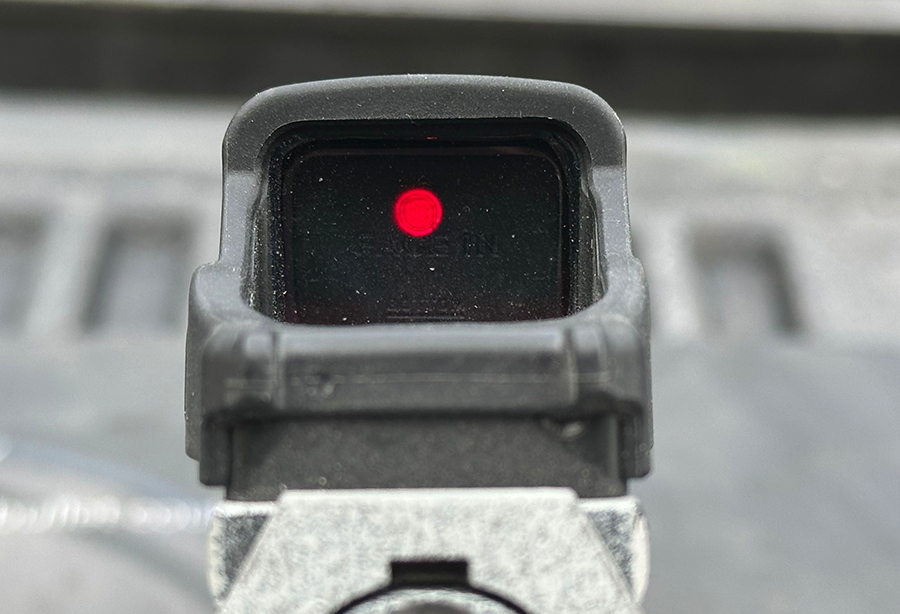

For my part, I’m nearsighted and I can see the Accur8 tritium front sight on my carry pistol clearly without the need for prescription glasses. However, if I’m looking through any optical sights, like the EFLX red dot from EOTECH, and I don’t have my glasses on, the reticle is fuzzy. With my glasses on, the dot is clear, but the front sight’s slightly fuzzy, even when I try my best to focus on it. You might have similar issues.

Red Dot Solutions

Many shooters with older eyes or vision issues have found that an illuminated dot optic provides them with a better reference point than a traditional iron sight setup. That’s great. However, many folks who have switched from irons to dot sights discover that finding the dot can sometimes slow them down. Those shooters are used to looking for the front sight and when they start using a red/green dot optic, they look for the aiming dot like they would a front sight. The time lag can be frustrating.

Going back for a moment to foveal vision and focusing at different distances, when we’re using iron sights we have three things in front of our eyes on three different planes; rear sight, front sight, and target. We know from hundreds of years of experience that when using iron sights, the best way to hit the target is to put the foveal vision focus on the front sight. However, in the panic of a lethal force encounter, the tendency is to put all the focus on the threat.

It takes hundreds of hours of dedicated training and practice to overcome this tendency and see the front sight clearly under extreme stress. When faced with the adrenaline rush brought on by a deadly force encounter, those who own guns but don’t train will focus hard on the threat while looking over the top of their gun. The end result is predictably low impacts resulting in either peripheral hits or complete misses. None of this is new and trainers have been aware of it for decades.

Now, with a handgun equipped with a red (or green) dot optic, we don’t need to focus hard on an object sticking up right over the muzzle. Instead, what we can and should do is to put our deliberate focus on the target and then present the gun/optic combination into our target picture. When shooters who are used to iron sights find that the dot seems to take more time to get on target, it’s because they’re trying to put their focus onto the dot and then move it onto the target.

What competition shooters learned decades ago when red dots were big, heavy, and expensive, was that the best way to use that setup was to put their focus on the target, draw their pistol, and the millisecond their brain perceived the aiming reticle to be on target, press the trigger. Rather than shifting their foveal vision focus from the dot to the target to the dot, we keep our focus on the target and when the illuminated reticle is perceived and becomes a part of the target picture, that is the “go code” for our brain to command our trigger finger to press.

The Dot Focus Issue

Keep in mind, just as shifting focus between the rear sight and front sight slows down the process, so too does shifting focus from dot to target to dot or vice versa. If you find that your visual tendency is to try and focus on the dot rather than the target, one trick is to cover the front lens of the optic.

You can use tape if you want, but there is a company called OpticGard that makes some useful optic protectors/covers. One of the features of these OpticGard covers is it’s a good option to cover the lens.

When you cover the front lens, in order to hit your target you need to keep both of your eyes open and focus on the target. When you present your handgun into the target picture, your dominant eye will pick up the reticle and your brain will put the picture together.

Training and practicing with your optic covered in this way will force you to get into the habit of focusing on the target and then superimposing the dot onto it. After you’ve practiced with a covered optic for a while, you can take the cover off and proceed. You might be surprised at how your proficiency with the optic has improved.

The Color Vision Issue

In the United States, the number of adult men with color vision issues or color blindness averages around nine to ten percent. I have two friends who told me that they had no use for red dot optics because their eyes can’t see the color red. However, green dot optics are a completely different color spectrum and both of my aforementioned friends can perceive the reticles with green dots. These gentlemen don’t see true green like those with color vision perceive, but the aiming point is there.

As mentioned above, as we lose the ability to see color, the red spectrum is the first to-go. For people with color vision issues, red or orange front sights will blend in with the gun, while the safety green or white front sights will stand out. Remember, when we lose color vision, black is always black and white is always white. If I were to recommend an iron front sight to a person with color blindness a bold, white front sight would be my suggestion.

Parting Shots

Before I let you go, just as we mentioned during the previous part one, adding new sights or optics to a handgun doesn’t make a gun more accurate. Installing a red or green dot optic on your handgun isn’t a shortcut around training and practice. Even if the optic is mounted directly to the slide, the aiming reticle is still in a different location than the front sight. If you expect to achieve proficiency and then mastery, you have to put in the time.

Paul G. Markel is a combat decorated United States Marine veteran. He is also the founder of Student the Gun University and has been teaching Small Arms & Tactics to military personnel, police officers, and citizens for over three decades.

“The near or close-up part of the lens is at the bottom and the distance viewing part is at the top.”

The next time you get glasses, you can ask them to swap that around so the “close-up part” is at the top and the “distance viewing part” is at the bottom. Most gun people with glasses never think about doing this.