With the terrible news of a major mass shooting in Australia , the debates about the efficacy of that country’s very strict firearms laws are arising with renewed focus once again.

At a surface level, gun control proponents seem to have quite the upper hand here. Since Australia’s expansive gun control efforts following the Port Arthur massacre of 1996, there have been few mass shootings, and the Bondi Beach attack this past weekend represents the first major one since Port Arthur. The United States in that timeframe has had dozens of mass shootings (or thousands, if you use the debunked Gun Violence Archive’s definition). By that standard, the gun laws put in place following Port Arthur, which included a mandatory buyback of around a million now-banned guns, were a smashing success.

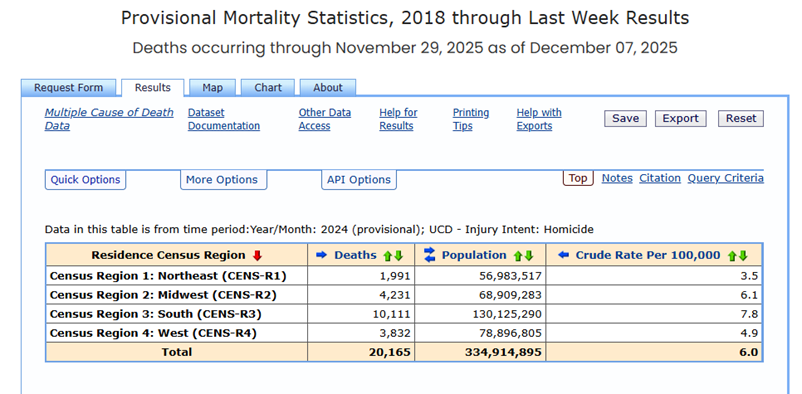

As for overall homicides, there were 448 victims in 2024 according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Given its population of about 27.5 million people, Australia can thus claim a low rate of roughly 1.6 homicides per 100,000 people in 2024. While the United States has seen a dramatic reduction in homicide and may be headed for record lows in 2025, we had 20,165 homicides in 2024, for a rate of 6 per 100,000. The US thus had a homicide rate nearly four times higher than Australia in 2024.

On suicide, Australia’s official rate was 12.2 per 100,000 people in 2024. While that beats the United States, it’s much less dramatic a difference than the homicide data, as the US had a rate of 14.6 suicides per 100,000 people in 2024 according to the CDC’s data.

In sum, Australia can boast far fewer mass shootings, a much lower homicide rate, and a slightly lower suicide rate than the United States. So does all of this prove gun control works, and if the US simply repealed the Second Amendment and copied Australian gun laws, we too would achieve similar levels of safety?

In a word, no.

There are four critical pieces of evidence missing from the discussion which either significantly weaken or outright defeat the claims that gun control is responsible for Australia’s success on mass shootings and homicide:

1. International mass shooting comparisons usually fail to take population differences into account;

2. Australia has always had a low homicide rate and very few mass shootings, including before its gun law changes following Port Arthur;

3. The United States and Australia have very different demographics;

4. Australia omits assisted suicides from its overall suicide data.

This article will take each point in turn. While the focus here is on Australia, a very similar analysis could be done for European countries and Canada.

1. International mass shooting comparisons usually fail to take population differences into account.

To begin with, we need to define what a mass shooting is, as there are various metrics of how to measure that term and what to include within it. I wrote an article on this topic previously, and so won’t reiterate it all here.

To summarize, the most expansive measure is the one used by the Gun Violence Archive, which counts any incident where four or more people are shot (not including the shooter) as a “mass shooting.” That leads to a tally of hundreds of “mass shootings” each year which are, in reality, personal disputes or gang violence, and not situations where an active shooter walked into a public place with the goal of killing as many random people as possible. For example, the current most recent entry is dated December 14, 2025, and involves four people injured in a shooting in a hookah lounge parking lot following a fight that broke out between them.

To be sure, shootings like that are a societal problem, but they’re not what anyone is talking about when they discuss the scourge of mass shootings. These sorts of incidents should be discussed with overall homicide and assault data, and not classified as mass shootings.

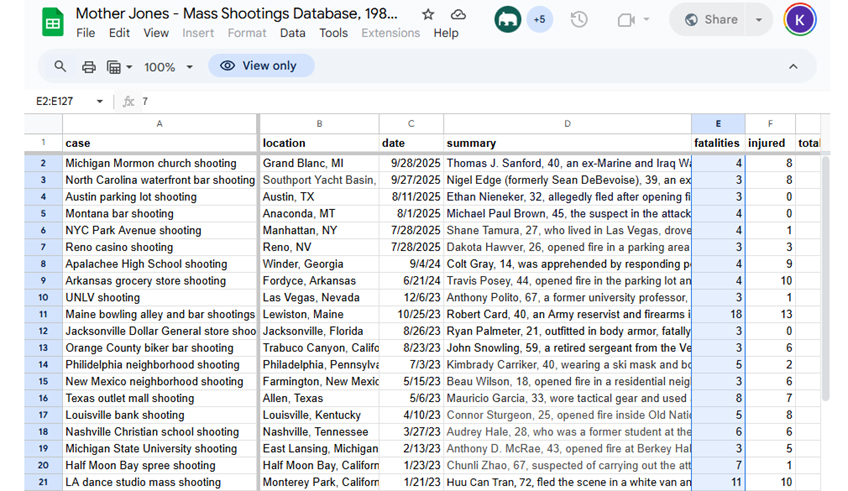

A far better and more relevant measure is the one Mother Jones maintains, which classifies as a mass shootings any event in which the perpetrator killed four or more people and it wasn’t a gang-related shooting, nor a domestic violence incident that took place in the home. That’s the definition we will go with for the purpose of this article.

Since 2000, Australia has had three shootings that fit this criteria. The United States has had, per the Mother Jones database, 127.

But the true measure isn’t 3 vs. 127, because Australia has a population of 27.5 million people, while the US has a population of about 342 million people, about 12.5 times as many as Australia. When you divide our mass shooting tally by 12.5 to account for that population difference, the difference is no longer 3 vs 127, it’s about 3 vs. 10. In other words, if the United States had the same population as Australia, it would experience one mass shooting every 2.5 years while Australia sees one every 8 year or so.

Three vs. ten is nothing to brag about, of course. Australia still has fewer mass shootings adjusted for population than we do. But failing to acknowledge the massive population difference between the two countries in any discussion comparing the two counties is misleading. It leaves the viewer or reader thinking that the United States has around 40 times more mass shootings than Australia, not only three times more.

The comparison is even more extreme with other countries. Denmark, for instance, has had two mass shootings since 2000 that fit the Mother Jones criteria. But with a population 57 times smaller than our own, Denmark’s rate of mass shootings is almost identical to that of the United States (though caution should always be taken when comparing such small sample sizes of rare events).

These sorts of population-adjusted rates should always be acknowledged, and then debate can resume on whether the remaining advantage Australia enjoys is due to its restrictive gun laws.

In sum, the United States’s population makes mass shootings feel more common than they actually are. With over 340 million people, there are just many more opportunities for these terrible events to occur, and when they do, they get lots of media coverage that makes them feel like they are constantly happening.

As a final note, there is some indication that there has been substitution in mass killing methods due to Australia’s gun control laws. When guns are harder to get, sometimes killers choose other methods. If we count attacks in Australia that meet the Mother Jones criteria using methods besides firearms (like arson, stabbing, or car attacks), Australia has had another five mass killings since 2000.

For example, in April of 2024, a man stabbed six people to death and injured 12 others at Bondi Junction, just two miles from where the Bondi Beach shooting occurred. A 2011 arson attack at a nursing home killed 11 and injured dozens of others. The United States has had a few non-gun mass killings too, though those occur at a far less frequent rate here. A fairer comparison would perhaps count all public mass killings in both countries and compare the resulting rates, but that’s an exercise for another day.

2. Australia has always had a low homicide rate and very few mass shootings, even before the Port Arthur gun control laws.

Following the Port Arthur massacre, Australia implemented a wide-ranging crackdown on firearms called the “National Firearms Agreement,” including confiscating and destroying over a million firearms. Semiautomatic rifles and shotguns are highly restricted, while other firearms like bolt-action rifles require licensing.

Gun control advocates in the United States point to Australia’s low homicide rate and mass shooting tally as proof that the National Firearms Agreement was successful. There’s a big problem with this assertion though: Australia has always been quite safe, even when its firearms laws were much more permissive.

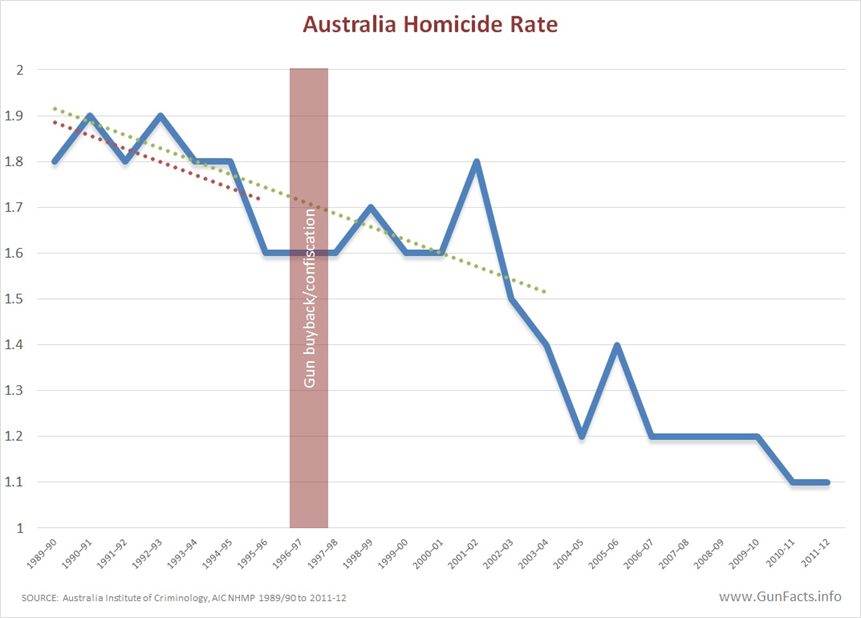

Australia’s homicide rate peaked at about 2 per 100,000 in the 1980s, and has generally stayed between 1 and 2 per 100,000 since then. As noted earlier, it’s at about 1.6 per 100,000 today. The homicide rate fell following the adoption of the National Firearms Agreement, but that drop began before its adoption, and if anything, the fall paused in the years immediately following those laws before resuming the decline in the early 2000s.

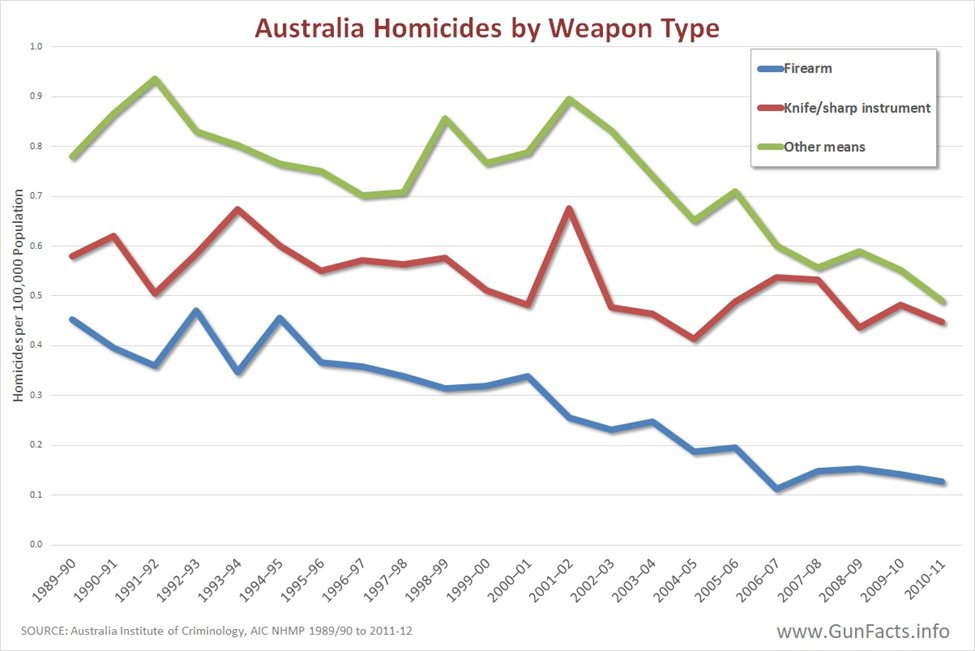

(Our friends at @gunfacts have put together a series of helpful charts in their page examining Australia’s gun laws, which I will borrow here.)

Still, that’s quite the decline, as the homicide rate basically got cut in half from 1990 to 2011. Clearly, whatever Australia was doing worked, even if the decline began before their reforms, right?

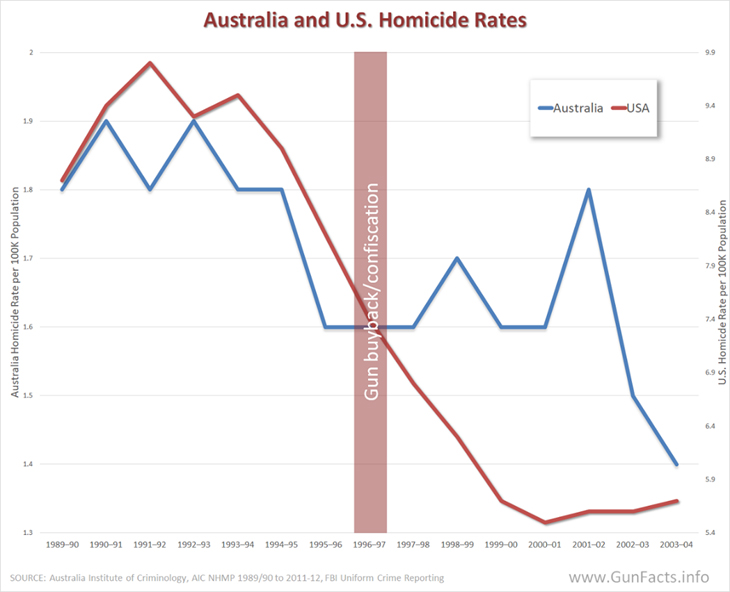

Again, the comparison to the United States during a similar time period is very enlightening. From 1991 to 2003, the United States also saw its homicide rate cut almost in half, and in fact, its decline was more rapid than Australia’s:

This was at the same time millions more guns were sold in the United States, as “the number of privately owned firearms in US increased from about 185 million in 1993 to 357 million in 2013.”

The key takeaway here is that while Australia was taking away a million firearms, the United States roughly doubled its firearm stock, while still cutting its overall homicide rate at the same pace Australia did.

Also cutting against the idea that the National Firearms Agreement was responsible for Australia’s declining homicide is that all types of homicides declined, not just firearm-related homicides. This isn’t what you would expect to see if a strict gun law was the cause of the decline, as gun homicides would drop, but other types would stay roughly the same.

In short, there’s very little evidence that Australia’s gun laws caused a decline in homicide. The United States saw a very similar rate of decline at the same time, and even in Australia, non-firearm-related homicides dropped in roughly equal measure as firearm-related homicides.

But what about mass shootings?

As discussed previously, Australia had three mass shootings from 2000 to the present that fit the Mother Jones criteria. But what about the 25 years prior to Port Arthur? In total, there were five shootings that fit the same criteria.

On the one hand, five is obviously more than three. But on the other, we’re talking about extremely rare events here, and five in 25 years isn’t dramatically more than three in 25 years. By any measure, Australia has always had very few mass shootings, as they have always been a rare occurrence in that country regardless of its gun laws.

3. The United States and Australia have very different demographics.

In measuring the homicide rates of different countries, there are a number of factors to control for before you can try and isolate one factor as the differentiating cause of a particular problem. In comparing Australia to the United States, an obvious difference is in the very different demographics of the two countries.

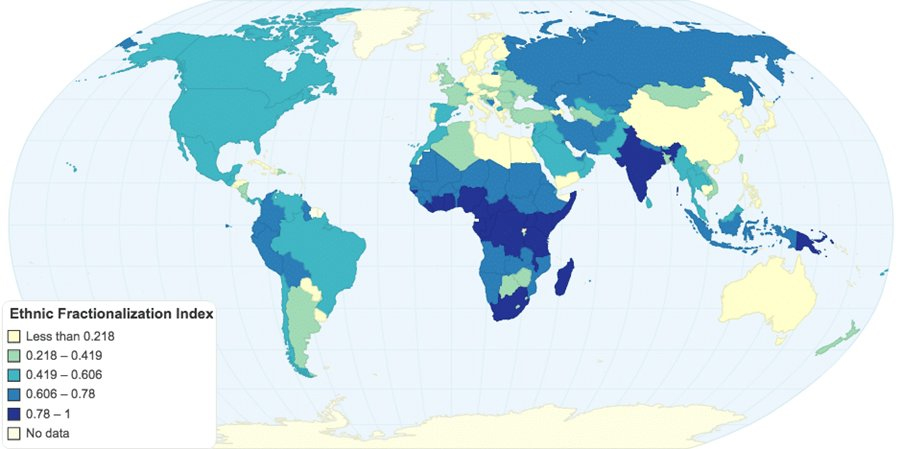

The United States is a major melting pot, which brings the benefit of economic dynamism, but also considerable tensions that can lead to increased violent crime. Australia is essentially the opposite in terms of its diversity. According to the Ethnic Fractionalization index, it’s one of the least diverse counties in the world.

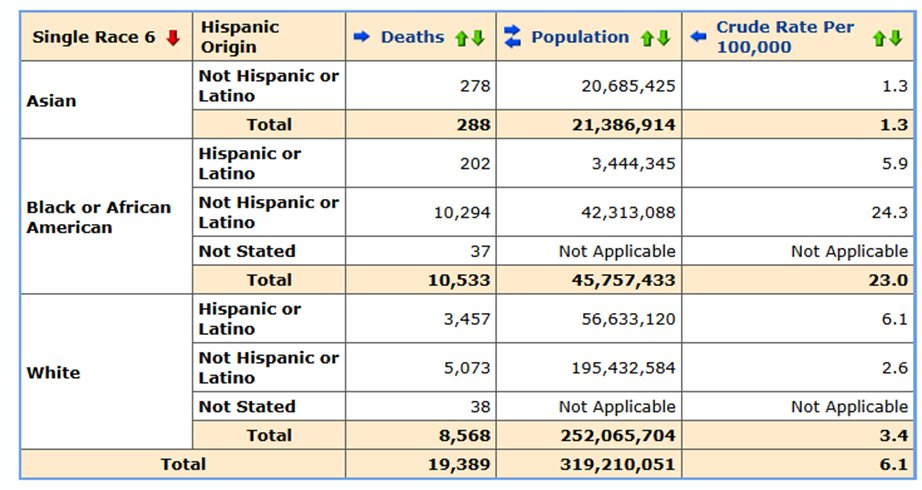

That’s important because homicide isn’t equally distributed among racial and ethnic subgroups in the United States, a topic which was the subject of another one of my articles.

Non-Hispanic white Americans had a homicide victimization rate of 2.6 per 100,000 in 2024, while Asian Americans came in at 1.3 per 100,000. Asian Americans are thus about as safe as Australians in terms of homicide rates, while white Americans have a rate about 1 per 100,000 higher than Australia.

The reason the United States has an overall homicide rate roughly four times higher than Australia’s is because other groups don’t fair as well. Latinos have a homicide rate of about 6 per 100,000, and black Americans have a shocking rate of 24 per 100,000.

Note that this isn’t correlated with gun ownership by race. It’s not as if Black Americans simply own more guns per capita and that explains their higher homicide rate. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2017, 49% of white Americans reported owning a gun or living with someone who does, while just 32% of black Americans said the same. (Pew did not inquire into Asian Americans in the poll).

White Americans are probably the most well-armed civilian demographic group on the planet, yet their homicide rate doesn’t reflect the assertions of gun control proponents that high gun ownership equals high homicide rates.

If the United States had Australia’s demographics (i.e., if the country were more overwhelmingly white and Asian), its homicide rate would be far lower, likely coming in somewhere around 2.0 to 3.0 per 100,000, depending on how you classify each subgroup. Grok tells me it would be about 2.9 per 100,000, though I can’t vouch for AI having handled everything correctly.

That’s still higher than Australia’s homicide rate of 1.6 per 100,000, and we can certainly argue over whether that difference comes down to firearms access. But simply substituting an Australian demographic makeup would cut the United States’ homicide rate by more than half, and considerably shrink the difference between the two countries in that measure. That’s why controlling for such differences is important before discussing the efficacy of gun control laws, or a number of other policy debates.

Comparing American and Australian homicide rates without accounting for this major difference between the countries is misleading to the point of outright dishonesty.

4. Australia omits assisted suicides from its overall suicide data.

As mentioned earlier, Australia’s suicide rate is slightly lower than that of the United States, coming in at 12.2 per 100,000, compared to 14.6 per 100,000 in the U.S. While not as big a difference as in homicides, this too is sometimes pointed to as a success of tighter gun control laws, as suicide is made easier when a firearm is available.

A separate article of mine covered the intersection of suicide and firearms in the United States, and the debate around that. But one of the points I made in that article is how Canada hides its considerable suicide rate behind legalized assisted suicide, which it doesn’t count in its official suicide tallies. When that’s factored in, Canada’s rate rose from 11.2 per 100,000 to 45 per 100,000.

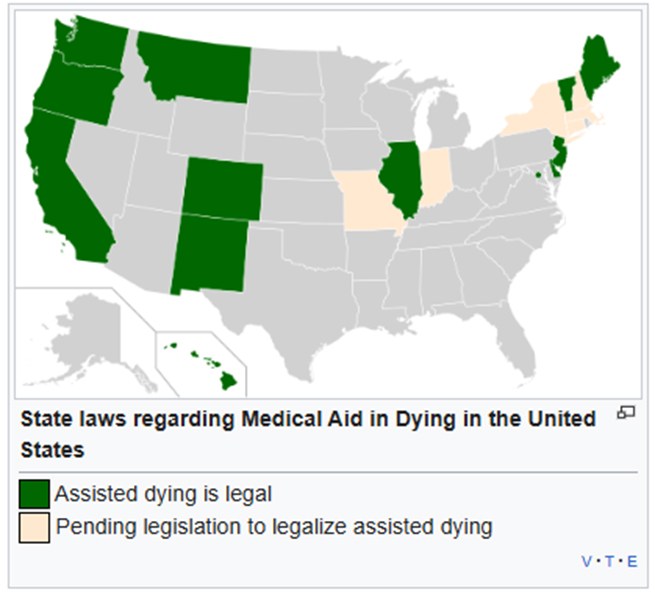

Only 11 states have legalized assisted suicide, meaning that for most Americans, it’s not an option. It therefore stands to reason that at least some of our overall suicide rate would become assisted suicides were that option more widely available here.

Australia has assisted suicide everywhere but its Northern Territory as of November 2025. In 2023 to 2024 (the data on assisted suicide is broken down by fiscal year), a total of 2,131 Australians used assisted suicide to end their lives. When you add that to the government statistic of 3,307 suicides in 2024, the overall suicide rate rises from 12.2 per 100,000 to 19.8 per 100,000, making it significantly higher than the United States despite its stringent gun laws.

Conclusion

As stated at the outset, Australia is a very safe country. But the case for its gun laws being the reason for that safety is flimsy at best. Australia is smaller, less dense, and less diverse country than the United States. Its murder rate was low long before it adopted its current strict gun policies, and mass shootings have always been a very uncommon occurrence. When looking at the data in totality, it looks like Australians surrendered their right to arms without seeing much of a statistical gain in overall safety, especially considering the US has seen similar rates of decline in homicide without making the same compromises on our rights.

Kostas Moros is Director of Legal Research and Eduction for the Second Amendment Foundation. This post was adapted by SNW from an article posted at X.

Note: This work is made possible by the Second Amendment Foundation. If you enjoy this article consider becoming a member or donating.

STOP . CONFUSING . ME . WITH . THE . FACTS ! ! ! ! !

Commentary test.

And, as in Canada, the suiciders simply found another method of succumbing so the overall rate rate did not decline.

Furthermore, if 9 Democrat-dominated large cities are eliminated, the US non-suicide homicide rate per 100,000 is 1.6 which is virtually identical to Australia’s 1.7.

Furthermore, the American colonies were founded by religious and political dissidents. Australia was founded as a Penal colony. American’s had a successful revolution in the 1770s. Australia had a FAILED revolution in December 1854 (almost 100 years later). Americans are independent minded but Australians are inured to compliance.

See Kopel THE SAMURI, THE MOUNTIE, AND THE COWBOY.

The successful American revolutionaries, before they would agree to a new CROWN (central government), insisted on a Bill of Rights including a strong Right to Keep and Bear Arms.

you are in reality a good webmaster. The web site loading velocity is incredible.

It kind of feels that you’re doing any unique trick. Moreover, The contents are masterpiece.

you’ve performed a fantastic process in this topic!