Recently we covered the difference between MILs and MOA, which causes some confusion among shooters. In the last edition, I talked about reticles and focused on how Christmas tree-style reticles have evolved. Now it’s time to move on to some of the common myths and misconceptions about optics, specifically, objectives. But first, some fundamentals again.

The Basics

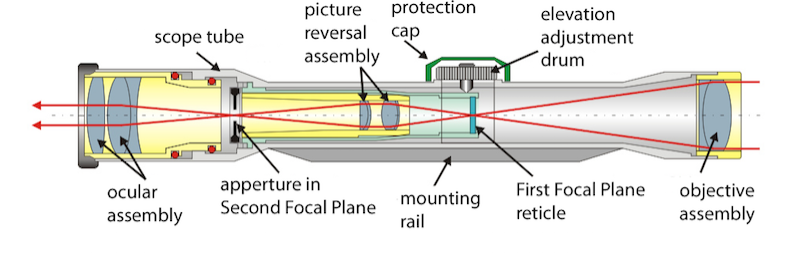

A scope consists of three optical components. First, the objective is the part of the scope in front of the turrets. The erector is the system that supports the objective and is positioned in front of the eyepiece. Finally, there’s the eyepiece itself. Each optical system contains a series of lenses that direct the image back to the human eye.

Another common term used in optics is aberration to better understand how light is transmitted to your eye. Aberration is the failure of light rays to converge at one focus point because of limitations or defects in a lens. Essentially, when light hits the first lens of a riflescope, the light begins to bend and refract in undesirable ways. A good scope uses tools to correct that, creating a clearer, brighter target picture.

Then there’s the focal plane. The reticle of an optic can be placed in one of two different focal planes—either in front of the turret assembly or behind. A reticle in the rear, or second focal plane maintains a constant size as the lens is zoomed in or out. Front, or first focal-plane optics have reticles whose size increases or decreases proportionally as magnification is increased or decreased. For more on this, see our earlier article here.

Scope Objective

A common myth about riflescopes is that the larger the objective bell in the front, the more light a scope gathers. That’s not really true. Scopes aren’t funnels. They can’t break the laws of physics. In reality, light gathering depends on the number of lenses a scope contains, the makeup of those lenses, and the coatings applied to them.

Increasing the quality of lenses and their coatings increases the percentage of light a scope transmits to the shooter’s eye. Remember, once light hits a barrier — in this case, a lens — it does all sorts of wonky things. The components built into the optical system help fix those irregularities.

Aberration, as defined above, is one of those things that happens. A good riflescope fixes aberration. Riflescopes with large objective lenses have to work harder to correct aberration because of the harsher angles the larger lenses create.

To go a little deeper, high-magnification optics perform well with large objective bells and long main tubes. That’s why low-powered variable scopes (1-6X, 1-8X, etc.) are very capable with relatively small front objective lenses and short main tubes. Scopes with a magnification of 3-9X that use a 50mm objective instead of a more conventional 40mm bell aren’t really gaining more, comparatively. If anything, the image may “appear” better (which has more to do with the exit pupil, which is coming in a future article), but the optic is losing depth-of-field.

Depth of Field

DOF is like watching standard-definition TV compared to 4K UHD. The same image is shown, but in the 4K version, it has greater depth and sharpness. Returning to the 3-9X40 vs 3-9X50 example, the 3-9X50 will have realtively lower image quality and DOF because the manufacturer isn’t compensating for the aberration introduced by a larger bell in the same length of scope. Larger lenses create harsher angles for light to pass through, which requires more internal lenses to correct.

So, when is it appropriate to have a larger objective lens? For long-range or PRS-style shooting, a 5-25X scope with a 50 to 56mm objective and a long main tube makes sense For tactical or offhand shooting, an LPVO scope with a 24 or 30mm objective works better. For hunting, magnification ranges of 3-9×40, 2-12×42, or 3-18×44 work well, as long as the scope is well-designed.

Zooming Out

The subject of riflescopes is murky and can be difficult to navigate, especially as the options available to the consumer increase almost every year. The market seems almost saturated with optics, both good and not so good. The user needs a better understanding of why one is better than the other if they’re going ot spend their money well. When buying a scope, it is all about having a plan in place. Knowing the budget, reticle style, measurement system, and what to look for will help to enhance your experience in the type of shooting you plan to do.

I would like to think that I am incredibly well-informed when it comes to optics:

I have researched optics in depth for shooting applications, terrestrial spotting applications, photography, and intensive astronomical applications.

I am well versed in basic Physics including both the particle and wave properties of light.

I am familiar with glass and lens properties (such as chromatic aberration).

I am aware of “fully multi-coated” lenses and why that is important.

I am familiar with “diffraction limited” optical systems.

I know all about exit pupils.

Having said all that, I have never heard of “depth of field” (which goes to show that no matter how much you know or think you know, there is always a LOT more to learn). I will have to research depth of field.

Okay, I researched “depth of field”. That refers to the range of distances that an optical system can focus simultaneously. For example, depth of field is an important factor if you want your optic to simultaneously keep very close (relatively speaking) and very far (relatively speaking) objects in the same field of view in sharp focus.

When it comes to rifle scopes with fixed focus, in reality you focus your scope so that distant objects are in sharp focus. At that point “field of view” simply refers to how close an object can be and still be in sharp focus. In my experience with rifle scopes, everything past 30 yards (give-or-take) is in sharp focus. Personally, I don’t care if objects within 30 yards (give-or-take) start to become blurry because they will be plenty large and discernable for accurate shooting.

In my opinion, light gathering capability and exit pupil are vastly more important considerations in a rifle scope. That being the case, I recommend that people optimize their choice of optic for light gathering and large exit pupils–which means larger objective lenses for higher magnifications.

(Note: all of my optical applications have been fixed objects at very long distances, thus “depth of field” was/is not a factor and I had never learned about it.)

Regarding light gathering capability and exit pupils with optical systems:

Exit pupil refers to the diameter of the cylinder of light exiting the scope and entering your eye. The human eye at maximum dilation opens up to about 7mm in children and somewhat less as we age. In order to see as much detail as possible, we want the scope’s cylinder of light to shine on as many receptors (rods and cones) in our eyes as possible, especially in low light. Since our pupils dilate to their maximum diameter of 7mm in low light, that means (ideally) we want our scope’s exit pupil to be 7mm under maximum magnification. In that situation, the image illuminates as many rods and cones in our eyes as possible and gives us the most detailed image possible.

Thankfully, the method to determine an optic’s exit pupil is super simple–simply your objective lens diameter divided by your magnification. For example, if your magnification is 6 times (e.g. 6x) and your objective lens is 42mm diameter, your exit pupil is 42mm / 6x == 7mm. The practical implication of that example is that your scope’s exit pupil will shrink to less than ideal as you increase magnification beyond 6x, and your eye will not be able to perceive/resolve as much detail. Images will also start to darken. (Continuing with the previous example scope with an objective lens that is 42mm diameter, going to 9x magnification would create an exit pupil of 42mm / 9x == 4.7mm which is less than ideal.)

So, the takeaway is simple: choose a rifle scope with the largest diameter objective lens practical/possible keeping in mind your goal of an exit pupil of 7mm at the highest magnifications.

“Having said all that, I have never heard of “depth of field””

Sure you have, you have just heard about it in different contexts terminology applied specifically – for example: ‘focal plane’, ‘focus range’, ‘focus axis distance’..