Now we come to the American battle rifle that closed out the Cold War; the M16A2. How and why did the M16A1 become A2 and what was the difference? In order to address that, we need to go back to the United States involvement in Vietnam from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. While the United States military entered the conflict with M14 rifles, by the time that the Battle of Ia Drang Valley occurred, they were equipped with the new M16A1 rifles which had a full-auto selector.

I recall reading a book about modern military arms in the late 1980s and coming across a section by the author where he stated that for every enemy KIA in Vietnam some 50,000 rounds were fired. To me that seemed astronomical. Of course, the number was an “estimate” but even if the estimate was off by five to ten percent, that would still seem to be a tremendous waste of ammunition.

Many lessons were taken from the Vietnam conflict which happened to be the last American war to use conscripted soldiers (draftees). During the down time between the end of the hostilities in Vietnam and smaller operations such as Urgent Fury in Grenada and Just Cause in Panama, the US Army and the entire DoD considered the successes, failures, and areas for improvement moving forward. Remember, Vietnam was just one of the proxy wars during the overall Cold War era.

Author’s Note: The rifle featured in the photos of this review is actually a new model SA-16A2 from Springfield Armory which, save the Class III burst option, is as close to an exact replica of the M16A2 as you can get today.

M16A1 becomes the M16A2

While it was Robert McNamara and his “whiz kids” who force fed the AR-15 to the DoD during Vietnam, in the quiet times of the late 70s and early 80s it was the United States Marine Corps chance to have a say in things. Colt’s Manufacturing Company was the prime maker of the M16A1 and they took the suggestions from the Corps when they made the upgrades.

First of all, no one in the Army or the Marine Corps wanted to go through the drastic change that they had experienced with the US Military switching from the Garand-action M14 in 7.62mm NATO to the M16A1 Stoner-design in 5.56mm NATO. The 5.56mm NATO cartridge was not going anywhere and the men already understood the manual of arms for the M16. They wanted an ‘improved’ rifle, not a ‘new’ rifle.

Therefore, the United States Marine Corps, with a proud tradition that “every Marine is a rifleman” wanted a rifle that was better suited for precision marksmanship. The Corps wanted to focus more on one shot/one kill versus the flip it to auto and “spray and pray” which had become the SOP in the jungles of Vietnam.

When the US DoD tabulated the 50,000 rounds of every KIA statistic, the logical solution was to remove the “happy switch.” Rather than take away “auto fire” altogether, a compromise was made. The new A2 would have a “burst” option; burst being 3 rounds per press of the trigger rather than the whole magazine all at once.

M16A2 Specifics

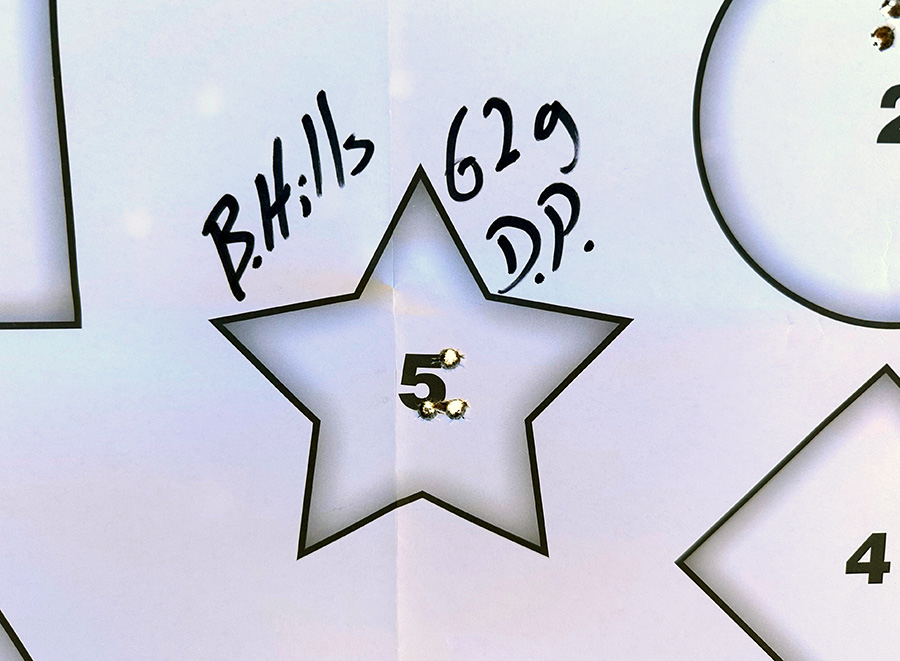

In order to fit the bill as a marksman’s rifle, the barrel on the A2 was made thicker or heavier and the rifling was changed from the original 1/12 RH twist to a 1/7 RH twist to make better use of the 62 grain projectiles from the new SS109 and M855 ammunition.

While the “A frame” front sight housing looks the same as the A1, the A2 front sight post is squared and the adjustments are quarter-click versus the round front sight post with five click adjustments on the A1. The front sight housing maintained the standard bayonet lug for the M7 version. At the rear of the carrying handle, the A1 rear sight was altered from a “windage only” design to the brand new A2 rear sight that allowed for both windage and elevation to be adjusted.

It should be noted that the BZO (battlesight zero) procedure for the A2 remained the same as the A1. For BZO, the rear sight elevation knob or drum, depending on where you learned the vernacular, was bottomed out all the way down.

Most models would allow the user to set the drum at “8/3 -2” or 2 clicks below the 8/3 marking. The rear sight aperture on the A2 has a small peep and a large peep that flips back and forth. For BZO, you use the small peep and line up the windage marker on the large peep with the marker on the base of the rear sight housing.

The front sight post should be flush with the front sight housing to begin the BZO procedure. Additionally, rather than use the tip of a 5.56 cartridge to adjust the windage wheel on the A1, a dedicated windage knob was included on the A2.

In the 1980s, the Marine Corps Rifle Qualification course included distances of 200, 300, and 500 yards with the rifleman using only a sling for support. At 200 yards, Marines fired from sitting, kneeling, and standing positions at a black bullseye target. At 300 yards, Marines fired from sitting and prone and then they were allowed to fire all their rounds from prone at 500 yards. The 500 yard target was a black human-sized silhouette. For comparison, when looking through the iron sights of an M16A2 rifle, a human silhouette is the width of the front sight post.

In order to make use of the aforementioned shooting positions, the Marines wanted a longer stock. The A2 stock is ⅝ of an inch longer and the A1 with a serious diamond pattern texture on the butt plate. The texture allows the stock to dig in and grip the shooter’s shoulder.

The pistol grip was also altered to the A2 style with the finger groove or the bump that separates the middle finger from the last two. Was this really necessary? Who knows, but it was new. Also, from an economic production standpoint, rather than produce left side and right side handguards, the new handguard design for the A2 utilized two identical handguard pieces. While that might not seem like a big deal, when you are producing a million handguards, it is.

Out at the muzzle, the “birdcage” flash hider on the A2 has openings only on upper or top 180º with the bottom being solid. This reduces the dust signature when the rifle is fired from the prone as well as pushing down against the natural rise of the barrel during recoil.

Also, it should be noted that the “brass deflector” feature on the upper receiver was a product of the A2 upgrade. While the brass ejection was never a problem for right handed shooters, for lefties firing the M16A1, you might get a hot piece of brass in your face.

STANAG 30 Round Mags and New 5.56mm Ammo

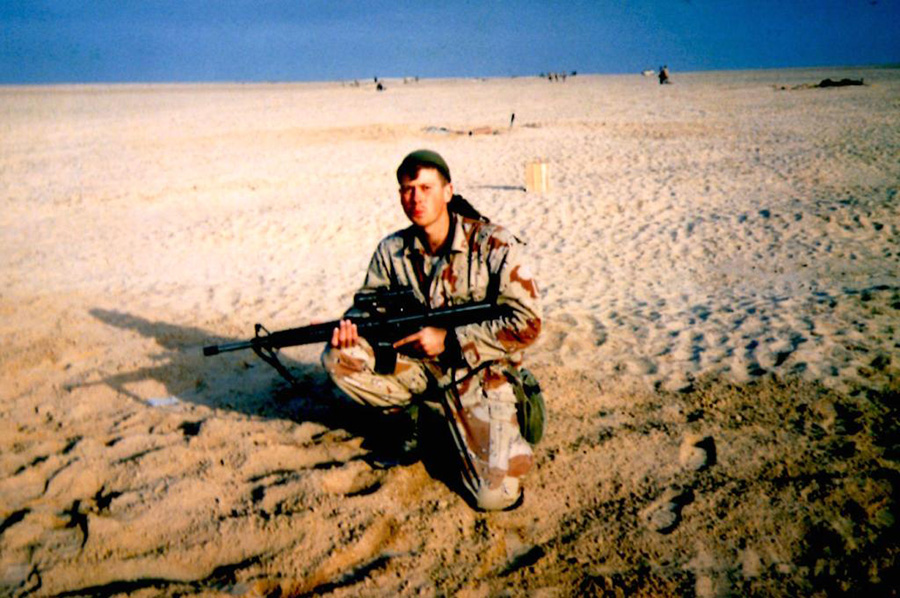

By the time the United States Marine Corps officially adopted the M16A2 rifle in 1983, 30 round, aluminum STANAG magazines for the M16 had become standard issue. The United States Army did not adopt the M16A2 until 1986 with many Reserve and National Guard units keeping their A1s well into the late 1990s. During the deployments to Operation Desert Shield / Storm, the active-duty units had A2 rifles while the activated reservists and guard units had the A1.

While you might be thinking, “Who cares, they are all 5.56mm rifles” the truth is that the 1/12 rifling of the A1 did not provide the stability desired for the new issue 62 grain projectiles in the SS109 and M855.

Did this make much of a difference? Considering the majority of enemy casualties in Desert Storm came from artillery, rockets and bombs, probably not. It would not be until the Global War on Terror when such an issue would be truly relevant. However, by that time, the US Army had moved on to the M4 and the Reserve and Guard units had M16A2 rifles.

Interestingly, there was a lot going on in the early 1980s in the Army and Marine Corps. The M81 Woodland camouflage pattern was officially adopted in 1981 and the slant pocket OD green uniforms were replaced by Woodland BDUs or “cammies”.

Interestingly, there was a lot going on in the early 1980s in the Army and Marine Corps. The M81 Woodland camouflage pattern was officially adopted in 1981 and the slant pocket OD green uniforms were replaced by Woodland BDUs or “cammies”.

In 1983, the PASGT (Personnel Armor System for Ground Troops) was adopted. This was a two-piece system with the new Kevlar helmets that replaced the old steel versions and an all Kevlar protective vest that vets simply called their “flak jacket”.

History

In the end, the Marine Corps got what they desired, a battle rifle that could put single rounds on target out to 500 yards using iron sights with predictable reliability. The Army got a rifle that had a burst mode so their soldiers would have to slow down and not just mag-dump in the general direction of the threat.

Interestingly, the United States Navy fielded a version called the M16A3. This was essentially an A2 upper mated to a full-auto M16A1 lower receiver. As it was explained to me by a US Navy Small Arms instructor, “We don’t have the SAW (squad automatic weapon), so if we need suppressive fire, we just switch the A3 to full auto.”

As many of you will know, the M16A2 led to the Marine Corps’ M16A4 that was essentially the same rifle with a removable carrying handle attached to a Picatinny-rail upper receiver. The Pic rail upper is currently the standard configuration for most of the AR-style rifles produced in the United States. In order to make their Marines even more deadly at distance, the Corps purchased the TA31RCO, an Advanced Combat Optical Gunsight (ACOG) from Trijicon in the early 2000s.

While the M16A2 only saw combat in a few operations during the Cold War, it was the rifle that moved the United States military into the modern era.

Specifications: M16A2 Rifle

Caliber: 5.56x45mm NATO

Action: Gas-operated: safe/semi/burst

Capacity: 30 rounds (others)

Barrel Length: 20 inches

Overall Length: 39.63 inches

Weight (empty): 7.5 pounds

Furniture: High Strength, Black Polymer

Cost: $1249 MSRP for SA-16A2

Paul G. Markel is a combat decorated United States Marine veteran. He is also the founder of Student the Gun University and has been teaching Small Arms & Tactics to military personnel, police officers, and citizens for over three decades.