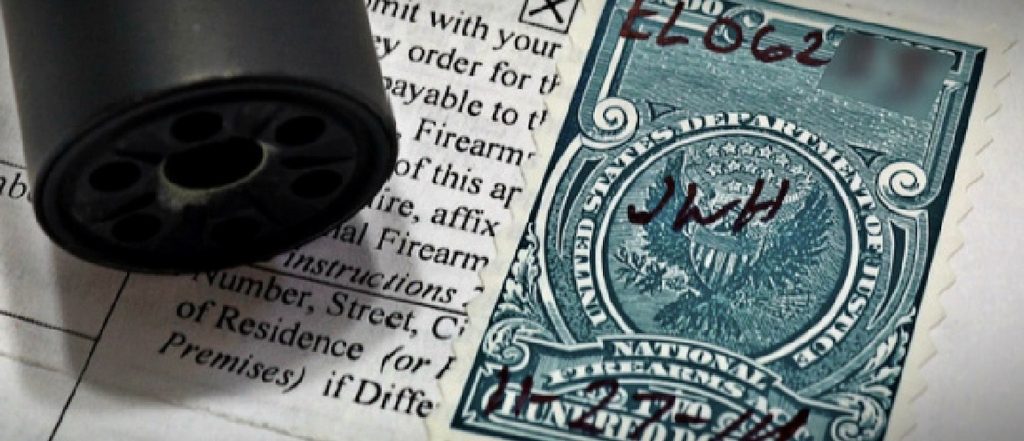

In the recent discussion around the potential removal of suppressors and short barrel rifles from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and its tax and registration requirements, a point was made repeatedly that if the tax was repealed but the registration aspect of the law stayed, the NFA would be illegal as it was only ever considered a tax law.

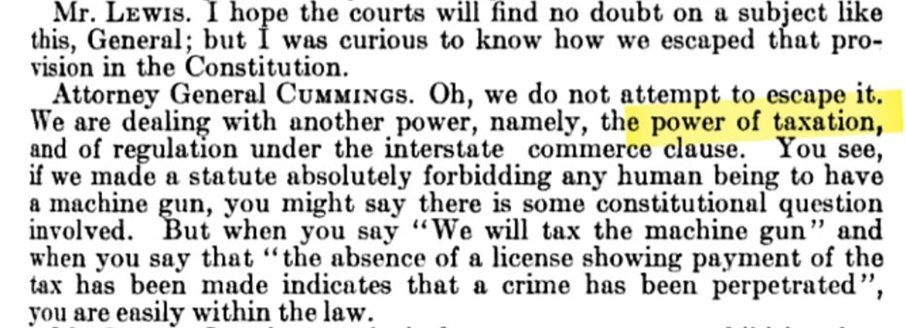

This is indeed correct. From its inception, the NFA was justified as a tax, with the registration being incidental and only existing ostensibly to ensure that the tax was properly paid for each NFA item sold. Then-Attorney General Homer Cummings was clear about this in his testimony to Congress during the debates over the bill in 1934:

Courts have consistently upheld the NFA and its registration provision on the grounds that it was a tax. Some who tried to challenge the law even argued that the tax was a pretext, with the real aim being to unconstitutionally restrict the arms included in the NFA.

The Supreme Court rejected this argument in 1937, just a few years after the NFA was first enacted in Sonzinsky v. United States . . .

“Petitioner. . .insists that the present levy is not a true tax, but a penalty imposed for the purpose of suppressing traffic in a certain noxious type of firearms, the local regulation of which is reserved to the states because not granted to the national government. . . But a tax is not any the less a tax because it has a regulatory effect. . . Here the annual tax of $200 is productive of some revenue. We are not free to speculate as to the motives which moved Congress to impose it, or as to the extent to which it may operate to restrict the activities taxed. As it is not attended by an offensive regulation, and since it operates as a tax, it is within the national taxing power.”

Ever since then, dozens of rulings have upheld the NFA on those same grounds. For example, in 2018 the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals explained that “the NFA is a valid exercise of Congress’s taxing power, as well as its authority to enact any laws “necessary and proper” to carry out that power” in United States v. Cox.

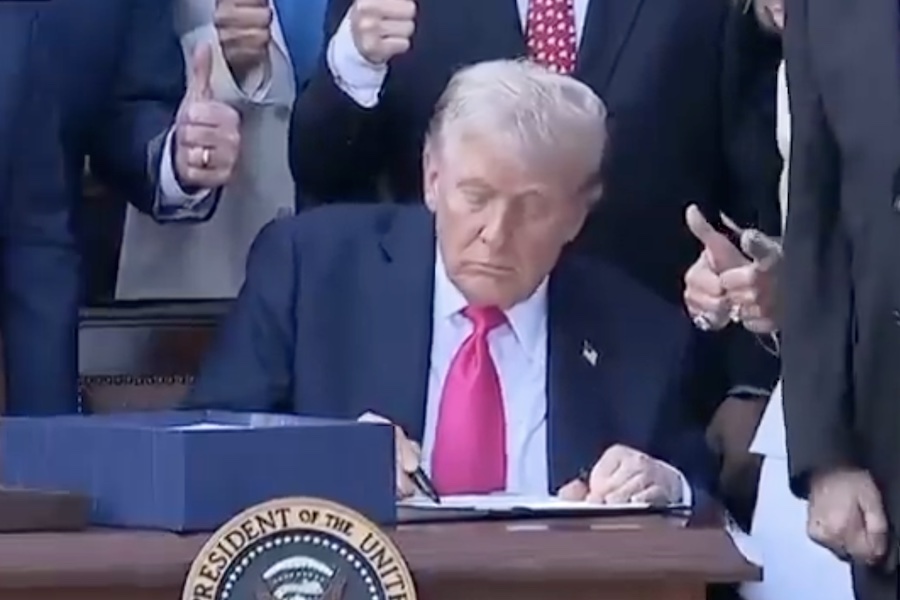

Unfortunately, the Senate Parliamentarian either didn’t grasp this or didn’t care, and struck the repeal of the registration requirement from the “Big Beautiful Bill,” deeming it unrelated to the budget and thus inappropriate for reconciliation under the Senate’s Byrd rule. Thus, only the tax was repealed, and so a registration provision that has been justified for over 90 years as necessary only to ensure that a tax was paid now finds itself seemingly vulnerable to legal challenge.

The first lawsuit filed against the NFA’s registration requirement unsurprisingly focused on this argument:

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which Congress and the President enacted on July 4, 2025, zeroes the manufacture and transfer tax on nearly all NFA-regulated firearms. That means the constitutional foundation on which the NFA rested has dissolved.

The plaintiffs in that lawsuit are right to try and exploit this open wound, given that courts will no longer be able to lazily uphold the NFA’s provisions on the grounds that it’s a tax now that the tax is gone for suppressors, short barrel rifles and short barrel shotguns.

One thing has been strangely missing from this whole discourse, however…the NFA never had any constitutional foundation, even when it was a tax. Taxes on arms, besides universally applicable sales taxes, are unconstitutional. The NFA should never have been upheld on taxation grounds in the first place, and other taxes such as the 11% assessed under Pittman-Robertson or California’s similar “sin tax” on guns and ammo, are also unconstitutional.

The Bruen Standard

To understand why taxes on arms are unconstitutional, a short summary of the Second Amendment analysis is helpful.

In 2022, the Supreme Court unequivocally reaffirmed the original public meaning standard for analyzing Second Amendment challenges set forth in District of Columbia v. Heller. Applying that test, the Supreme Court found that the Second Amendment protects the right to armed self-defense in public. The Bruen ruling reiterated that courts may not engage in any form of “intermediate scrutiny” or even “strict scrutiny” in Second Amendment cases and unambiguously instructed how a proper Second Amendment analysis is to be conducted by a reviewing court:

We reiterate that the standard for applying the Second Amendment is as follows: When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.”

Moreover, the government can’t simply proffer just any historical law that references firearms. Rather, when challenged laws regulate conduct or circumstances that already existed at the time of the Founding, the absence of widespread historical laws restricting that same conduct or circumstances indicates that the Founders understood the Second Amendment to preclude such regulation. In contrast, uniquely modern circumstances that did not exist at the time of the Founding call for an analogical analysis, based on the government’s proffered historical record. Outlier statutes do not satisfy the requirement. A law must be a “well-established and representative historical analogue.”

Courts may not uphold a modern law just because a few similar laws may be found from the past. Doing so “risk[s] endorsing outliers that our ancestors would never have accepted.” In fact, in Bruen the Court acknowledged that two pre-1900 state laws were insufficient to uphold New York’s carry restrictions, despite them being similar to the New York laws.

Finally, as to Bruen’s observation that “unprecedented societal concerns or dramatic technological changes may require a more nuanced approach,” this case is “fairly straightforward” because there is nothing new about arms, sales of arms, or taxation. In this sort of circumstance, the Supreme Court made clear that the “lack of a distinctly similar historical regulation addressing that problem is relevant evidence that the challenged regulation is inconsistent with the Second Amendment.”

Further support for this position can be found in the Second Amendment Foundation’s recent victory in a challenge to a California law limiting gun purchases to one per month. There, California argued that the limits were about stopping “trafficking” of arms, and one of the State’s experts stated that during the nineteenth century, “black markets in stolen goods” were a problem and so “Americans were concerned about firearms being sold into the wrong hands.” The panel rejected this argument because “the modern problems that California identifies as justification for its one-gun-a-month law are perhaps different in degree from past problems, but they are not different in kind. Therefore, a nuanced approach is not warranted.”

The NFA was justified for similar reasons; slowing the trafficking of arms the government considered dangerous. And just like California’s gun rationing law, its tax can only survive if there are “distinctly similar” laws like it in the Founding Era.

The History of Taxing Arms Pre-1900

Now that we know what we are looking for (laws that taxed firearms on a per-gun basis) we can look to see whether any distinctly similar historical laws before 1900 existed in sufficient number to justify modern taxes on firearms, such as the NFA. If any are “distinctly similar” to the modern NFA’s taxation provision, then that provision can be upheld. If not, it’s unconstitutional.

The earliest examples were not taxes at all, but rather fines for various violations. For example, a 1762 New York colonial law barred storing more than 28 pounds of gunpowder for those who lived in New York City, and if violated, a fine of ten pounds was assessed. To be sure, if someone chose to have more than 28 pounds of gunpowder, they had to store it at a designated “Powder-House,” which required a fee of three shillings per barrel of powder.

But that was less of a “tax” and more of a fee for using the powder-house. And in any case, it would only apply to those who wanted to have more than 28 pounds of gunpowder. Powder storage laws in general weren’t motivated by a desire for taxation or even gun control, but rather fire-prevention. Black powder was extremely combustible, and thus a giant safety hazard to the densely packed and mostly wooden cities of the time.

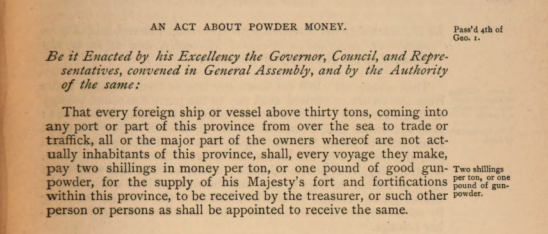

Other early examples demonstrate the limits of relying on colonial history. A 1759 New Hampshire law

required foreign ships coming into port to pay a tax of two shillings per pound of gun powder, in order to financially support “his Majesty’s fort and fortifications within this province.”

While superficially similar in that this was a tax on a necessary component to firearms – gunpowder – it’s not the same as the NFA’s far higher tax on each firearm or suppressor sold, and it only applied to foreign ships. Moreover, with similar laws being sparse or nonexistent, this seems to be an outlier, and “in using pre-ratification history, courts must exercise care to rely only on the history that the Constitution actually incorporated and not on the history that the Constitution left behind.”

In the Nineteenth Century, some laws started to appear that were slightly more similar to the NFA’s taxes. For example, an 1844 Mississippi law taxed Bowie knives at one dollar, and dueling or pocket pistols at two dollars. In modern dollars, that’s about a $43 tax on Bowie knives, and $86 on pocket or dueling pistols.

But to understand the difference here, it’s important to note what was not taxed: the prevailing combat weapons of the time.

Bowie knives and pocket pistols were seen as a criminal threat when carried concealed in this era, when those who carried lawfully did so openly. Some scholars even distinguished the “arms” protected by the Second Amendment from “weapons” which had no such protection. “Arms…is used for whatever is intentionally made as an instrument of offence…[w]e say firearms, but not fire-weapons; and weapons offensive or defensive, but not arms offensive or defensive.” – Joseph Bartlett Burleigh, The American Manual: Containing a Brief Outline of the Origin and Progress of Political Power and the Laws of Nations.

Other similar taxes existed around this late-antebellum time period, like an 1838 law from territorial Florida

which taxed dealers (but not buyers) of dirks, pocket pistols, and bowie knives $200 per year. That law also taxed those who publicly carried those specific weapons ten dollars per year. But again, these were not the “weapons of war” of their time, but rather concealable weapons that were used in petty crimes and personal disputes. Moreover, these taxes existed almost exclusively in Southern states and territories, and we have to be careful about relying too heavily on laws from the South given that Bruen looks for a national tradition.

Still, even if these laws were representative of the nation as a whole, there remains the problem that the taxes they enacted did not apply to military arms. A North Carolina law from 1856 makes this especially clear, specifically exempting pistols used for mustering from a $1.25 tax that otherwise applied on all pistols and bowie knives (though the tax only applied if the weapons in question were carried publicly, mere possession was untaxed).

Given these laws were careful not to tax guns like large revolvers, muskets, repeating rifles, and so forth that were used in warfare, how could they be “distinctly similar” to the NFA, which now applies to many arms that are useful in combat roles? For example, the M4 carbine is our military’s most common service rifle, and it has a barrel length of 14.5 inches. In the civilian context (and ignoring that it is also non-transferrable due to being a machine gun) that makes the most common military rifle a short-barreled rifle subject to the NFA’s tax, which applies to rifles that have barrels under 16 inches in length. (SIG SAUER’s M7 rifle that is set to replace the M4 will be no different, as it has a 13-inch barrel.)

Following the Civil War, many southern territories under reconstruction adopted “Black Codes,” which aimed to keep newly freed former slaves repressed, often with the assistance of the Ku Klux Klan. Strategic disarmament of black Americans was part of this nefarious project, as even President Grant complained to Congress. It’s no surprise that the Jim Crow era also saw a much more rapid adoption of taxes on certain weapons in the South.

Some of these were barely veiled at all. An 1867 Mississippi law assessed a tax of between five dollars and fifteen dollars on “every gun and pistol,” and if the tax was not paid, the Sheriff was obligated to seize that gun. This seems to be a very close NFA analogue, given that it applied to all guns, and the tax was considerable, ranging from $108 to $325 per gun in today’s dollars.

The trouble is, the law only applied in Washington County, Mississippi, and not the whole state. According to the 1860 census, Washington County was made up of 92% enslaved people, and even to this day is still over 70% African American. So this law wasn’t some general tax on guns, it was a racist effort to price freedmen out of firearms ownership.

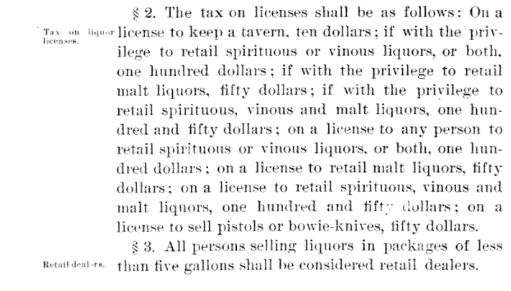

The last large category of taxes related to weapons and arms in the latter parts of the Nineteenth Century are occupational taxes on dealers. These were not assessed on a per-gun basis and are not similar to the NFA’s scheme. For example, an 1885 Kentucky law imposed a tax of fifty dollars on dealers of pistols and bowie knives.

To be sure, some historical taxes existed which arguably may lend support to the practice of including firearms in universally applicable taxes. An 1874 Virginias law included all firearms and other weapons in its listing of taxable personal property, but this was part of a broader tax that encompassed all sorts of personal property including horses, cattle, carriages, books, tools, watches, kitchen furniture, and much more. The tax was 50 cents per every hundred dollars in total value of all this personal property. This is somewhat similar to modern sales taxes, which apply to all goods sold and do not single out firearms for special taxation.

Conclusion: Taxes on Common Firearms have no Historical Support and are Thus Unconstitutional

While the above was certainly not a comprehensive listing of every historical tax on weapons and arms, it provides a representative sample of the sorts of pre-1900 laws that existed imposing such taxes. Given Rahimi asks us to look for the “principles that underpin the Nation’s regulatory tradition,” there isn’t much that can be concluded from these laws given the numerous deficiencies they suffer from.

They are not a national tradition, but rather a regional one existing primarily in Southern states. They didn’t usually apply to the prevailing combat arms of the time, but rather to concealable weapons like Bowie knives and pocket pistols. And most reprehensibly, they sometimes existed as part of Jim Crow to suppress newly-freed black Americans.

In sum then, while the NFA’s registration provisions are illegal and unconstitutional, we shouldn’t ignore that its taxation provisions are historically baseless and violative of the Second Amendment in their own right. The same applies to modern-day federal and state excise taxes, which can likewise point to no distinctly similar historical laws to support their continued existence.

This work is made possible by the Second Amendment Foundation. If you enjoy this article consider becoming a member or donating! Follow us at @2afdn

.

I remember way back when I was a kid some kerfuffle about some city taxing newspaper vending boxes. I don’t know how much these still exist, but there was a period where you’d see a dozen of these boxes chained together to a lamp post on street corners, and cities got tired of every free newspaper taking up space. The courts threw out their taxes on the grounds of targeting freedom of the press.

These gun taxes are exactly the same targeting. It shows the second class nature of gun rights.

Once upon a time, there was a tax and people wanted to be free…and the tyrannical British empire and the British loyalists go all upset.

One upon a time, there was a tax and people wanted to be free … and the government and SCOTUS said ‘No poll taxes’ and the Jim Crow tyranny Democrats and the democrat loyalists got all upset.

Once upon a time, there was a tax and people wanted to be free… and the republicans in congress got rid of it saying ‘no more NFA tax, and the last four years tyrant Democrats and the democrat loyalists got all upset.

Is it just me or is there a sort of trend with tyrants being upset because they can’t tax the people with unjust and, then and now, unconstitutional taxes to exercise natural rights?

A well written and well reasoned article. Thank you. One can hope that the court(s) in which the lawsuits are brought are not ruled by obama/biden/traitor judges. All we need is one patriot federal judge to declare the NFA of 1937 unconstitutional on it’s face to expedite it to SCOTUS

“Bowie knives and pocket pistols were seen as a criminal threat when carried concealed in this era…”

Bowie knives and pocket pistols are still seen as a criminal threat when carried concealed in this era in Blue States.

The use of taxation power to constrain fundamental rights secured by the BOR means every part of the Constitution can be taxed into ineffectiveness. The founders were not unaware of the danger of the Commerce Clause, but understood the propensity of State govts to attempt to punish other states economically (acting as if they were independent nations).

“The power to tax is the power to destroy”.

– – J. Marshall

A tax of zero amount ($0.00) is not “no tax”. Retaining the tax is important to anti-gunners, which is why they insisted on a numeric amount. Removal/repeal/elimination of a tax would legally result in “no tax”. Words have meaning, and govt employees are masters at word-smithing (“It depends on what “is” is”.) Leftists insisted on retaining the tax for a reason.

It is politically easier to raise, or lower, the amount of a tax, rather than create a new tax.

I think that there is a far simpler legal argument available: the U.S. Constitution’s Second Amender occurs later and must therefore supersede any earlier U.S. Constitutional provisions which conflict with it.

Sure, earlier in the U.S. Constitution it grants fedzilla broad authority to tax. Then the U.S. Constitution says that governments shall not infringe on our right to keep and bear arms. Since a tax is an infringement, it is not allowed on arms. Case closed.

You forgot mic drop!

I think the legal issue is whether the NFA is a tax issue, rather than a Second Amendment issue. Some of the information being gleaned from a number of cases and reports seems to indicate that ultimately, tax law can override provisions of the Constitution. If a tax on a constitutionally protected natural, civil, human right exists, the legal grounds for disputing the law must be based on taxing power, not whether the law infringes, or eliminates an existing provision to the contrary. Thus, the courts disregard the 2A arguments. Thus, “tax powers” cannot be used to support evicence of a violation of RTKBA. And ipse dixit, no tax law can be rendered unconstitutional.

Pole taxes are unconstitutional so taxing the 2A is also

How about a tax on free speech or going to church

“Pole taxes are unconstitutional so taxing the 2A is also

How about a tax on free speech or going to church”

Patience, patience. The law sometimes moves slow, but inexorably.