In our ongoing series on optics terminology and design, we’ve discussed the differences between MILs and MOA, the distinctions between Christmas Tree and BDC reticles, and the common misnomers and misunderstandings about objective bells. And most recently, we discussed one of the more critical and often misunderstood aspects of optic design—exit pupil. Understanding all of this can help you when searching for the optic that best fits your needs. This final part consists of a glossary of many of the terms you run across when discussing optics. While it might not be an all-encompassing list of terms, I hope it helps you understand and encourages you to learn more.

Aberration: Aberration is the failure of light rays to converge at one focus point because of limitations or defects in a lens. When light hits the first lens of a riflescope, the light begins to bend and refract in undesirable ways. A good scope uses tools to correct aberration and create a clear, bright target image.

Ballistic Solver: Common solvers include Applied Ballistics, Hornady 4DOF, and the Shooter App—all of which can be found in the app store on your smart device. These calculate the bullet’s flight path and predict holdovers based on the information input.

Bullet Drop Compensating (BDC): Our concept of BDC reticles emerged in the mid-2000s when Nikon popularized the idea. A BDC reticle includes holdover points along the vertical axis that mark different distances. The center of the crosshair usually begins at 100 yards (though this isn’t always the case). Essentially, if your target is 300 yards away and you’re shooting a standard cartridge—such as a .308—the shooter holds the reticle on the second BDC point. This system was effective enough that Nikon released many scopes with different configurations to suit various uses, including predator, tactical, and rimfire applications. Currently, nearly every manufacturer offers something similar. However, the reticle has its flaws. The main problem is that it is fixed in the second focal plane, meaning the reticle can only be used at a specific magnification, typically the highest power of the optic (depending on the manufacturer)—unless you’re skilled at calculating holdover points as magnification changes. BDCs are a fixed solution, so adjustments to parameters like caliber, temperature, and elevation are not easy to make. Ballistic calculators can “adjust” the holdover points but then lose the straightforward 100, 200, 300-yard references. For the average whitetail hunter in Ohio, where shots are often under 200 yards, a BDC reticle can be an effective tool.

Christmas Tree Reticles: An advanced reticle allows the user to hold over for elevation and wind correction based on ballistic data provided by ballistic solvers. These solvers use the shooter’s cartridge’s ballistics, combined with environmental data entered by the shooter (or obtained from devices like a Kestrel weather meter). These reticles are found in FFP optics; therefore, the holds stay consistent at any magnification setting. (Keep in mind, at low magnification, the reticle will be nearly impossible to see.) FFP reticles can be beneficial both on the firing line and in the field. As innovations emerge in long-range competition, those products and techniques are transitioning to hunting, with new classes of shooting competitions created to simulate field conditions, such as the NRL Hunter division.

Custom Dial System (CDS): This is Leupold’s response to Nikon’s and other manufacturers’ BDC reticle. Leupold applies the user’s ballistics and environmental information into a solver and then etches an elevation turret with yard increments. The benefit is that the turret adjustments are not impacted by the optic’s magnification. Turrets are constant, therefore fixing an adherent problem with a BDC reticle. Still, if a shooter wants to switch calibers or goes from hunting deer in Ohio to an Elk hunt in Colorado, the elevation impact will drastically change the dialing, thus a new turret will be needed.

Duplex: A reticle where the vertical and horizontal stadia intersect. The stadia are typically thicker at the edges and gradually decrease in size toward the center.

Elevation and Windage: The adjustment knobs on modern sporting optics. In modern optics, the lines don’t move independently of each other but instead move in a grid-like pattern.

Erector: the system from the eyepiece to the turrets.

Eye Relief: The fixed distance from the ocular lens at which the user can see the whole field of view. The image quality will suffer if the optic is too close or too far away.

Eyepiece: the rear portion of the optic that the user looks through. It also serves as the reticle’s focus adjustment.

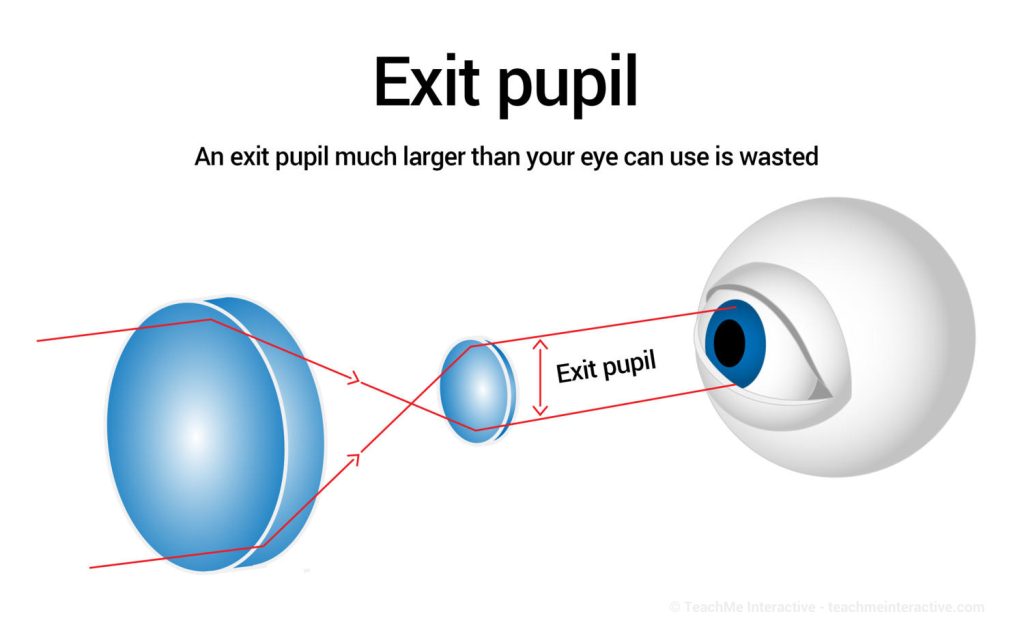

Exit Pupil: The exit pupil equals the objective bell diameter divided by its magnification. For example, on a 3-9×40 scope with the magnification set at its highest power, the exit pupil is 4.44mm.

The exit pupil of a scope directly influences how bright an image appears to the human eye. It relates to the relationship between the scope’s aperture and a person’s pupil size. In low light, a human eye’s pupil can widen from 3mm to 7mm. However, during the daytime, the pupil typically narrows to about 2.5mm when looking through a scope at targets hidden in shadowed vegetation. The closer a scope’s exit pupil size matches the eye’s pupil, the brighter and clearer the image appears. Therefore, a large objective bell creates a large exit pupil, but this does not always result in a brighter image because the human pupil cannot expand to match it, especially on a sunny day.

In this case, an objective bell’s aberration can be a problem unless the scope has the right lenses and coatings to address it. The main drawback is cost. A large scope with high magnification and a big objective bell that offers excellent optical clarity is expensive—usually over $2,000.

The exit pupil is most important at twilight and when shooting quickly. In low light, aim for an exit pupil that matches the eye’s pupil (remember, the eye’s pupil gets larger as daylight decreases). This helps the eye utilize all the available light from the scope. However, a large objective bell doesn’t always outweigh the downsides. Using a scope with a moderate magnification range and objective size, then dialing down the magnification, increases the exit pupil and preserves good optical quality and brightness while matching the eye’s pupil. When shooting fast, like in 3-gun matches, reducing magnification helps your eye transition smoothly between targets. A larger exit pupil gives the human eye more flexibility when focusing as the shooter shifts focus.

Field of View (FOV): The width of the area you can see through an optic. The higher the magnification, the narrower the FOV. Conversely, the lower the magnification, the wider the FOV.

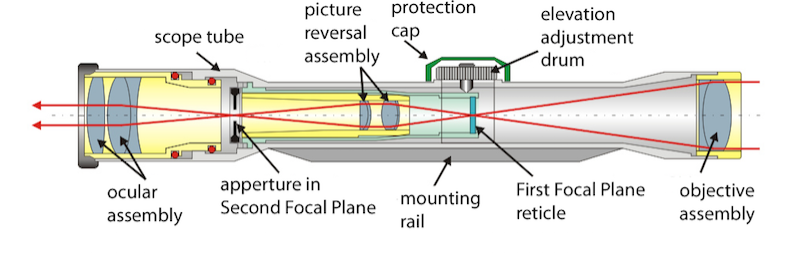

Focal Plane: The reticle of an optic can be placed in two different focal planes—either forward of the turret assembly or rearward. A reticle in the rear focal plane (also called the second focal plane) maintains a constant size as the magnification is adjusted. Front focal plane optics—or those in the first focal plane—feature reticles that grow and shrink proportionally as the magnification changes.

Illuminated Reticle: As the name suggests, the entire reticle or part of it is illuminated. While not ideal in bright conditions, illumination is better suited against dark backgrounds.

Minute of Angle (MOA): A circle has 360 degrees, with each degree divided into 60 minutes. This results in a total of 21,600 minutes in a circle. At a distance of 100 yards, 1 degree spans 62.83 inches. Therefore, 1 MOA— which is 1/60 of a degree— measures 1.047 inches. Usually, MOA is rounded down to a clean 1 inch. For most shooting purposes, this approximation works well. For example, at 1000 yards, 1 MOA is about 10 inches. The exact measurement, however, is 10.47 inches—a negligible difference.

Milliradians (MIL): A common misconception about MILs is that it is solely a metric system. This is not entirely accurate. A radian is a metric measure of angular distance, representing a part of a circle. Additionally, ‘ Milli’ means one thousandth, so one milliradian equals one thousandth of a radian. One radian is approximately 57.3 degrees—dividing 360 degrees by 57.3 gives about 6.2832 MILs in a full circle. There are 1,000 MILs in a radius and about 6,238.2 MILs in a circle. MILs are further divided into tenths for greater precision. At 100 yards, 1 MIL corresponds to 3.6 inches, and .1 MIL equals .36 inches. At 100 meters, 1 MIL equals 10 centimeters, and .1 MIL equals 1 centimeter. At a thousand yards, 1 MIL equals one yard, and at a thousand meters, 1 MIL equals one meter. While MILs are a metric unit, the systems function with both standard and metric measurements.

Mils can also be used for range estimation. The formula is as follows: Range (or distance to target) = target size / MILs. If you know the approximate size of your target, then you can calculate a rough range.

Parallax: a technical definition is the apparent displacement or difference in the perceived direction of an object when viewed from two different points that are not in a straight line with the object. Put simply, parallax is the error that occurs when shooting at long or short ranges without looking through the center of the rifle scope. This causes a displacement between the target and the reticle. If you are slightly off the centerline, it will cause point-of-impact shifts that increase with distance. Companies typically set parallax at 50 yards for rimfires or 150 yards for hunting scopes. Modern scopes often include a parallax adjustment on the side or the objective bell, commonly called side parallax adjustment or adjustable objective.

Objective: the portion of a scope forward of the turrets. The lens in the objective bell takes the incoming light and focuses it down to the first focal plane. Its size does not correlate to “light gathering” or image resolution (see exit pupil).

Zero Stop: The ability to lock in a fixed zero distance on the optic once it is sighted in. This allows for easy return-to-zero after dialing for longer ranges. This is ideal for precision or long-range optics.

Zooming Out

And that’s a wrap. Follow the links below to continue flipping through the articles in the series, and save this to your favorites bar for quick reference. I hope this series helps you in your pursuits.

- OPTICS 101: MILs vs. MOA

- OPTICS 101: CHRISTMAS TREES AND BDCs

- OPTICS 101: EXECUTING THE OBJECTIVE

- OPTICS 101: EXIT PUPIL

- OPTICS GLOSSARY PART 1: FROM A-E